OUR GRANDMOTHER’S KITCHEN

In the old days, cooking was a laborious affair. Those were the days before the invention of Thermomixers and blenders; the cooking tools were heavy and usually made from granite or brass. But our grandmothers swore that her grinding mill which was battered down and strained from strenuous utilization resulted in even tastier meals, as it bore the delicious nooks and crannies of years of pulverized ingredients. These were the internet-free days, where we could not Google or play a YouTube video for cooking instructions nor could we log on to an application on our phones and order a batch of ‘Nasi Lemak’ and ‘Ayam Goreng Berempah’ when a group of twenty cousins drop by for an unexpected visit. These were also the days where recipes, if passed down, were measured by how much they cost or by the length of your thumb.

Let us now take a short trip to our grandmother’s kitchen.

Weights and Measures

Weighing Scale

The measures used in the recipes handed down from our grandmothers and mothers were very different from those found in recipes today. Examples are the size of a thumb, a handful or fistful of ingredients. Often, there were no specific measurements given, just an approximation (“main agak agak sahaja”). Our grandmothers simply threw (campak) the ingredients into a pot and added more (tambah) if they felt the consistency or taste is not right. Sometimes cigarette tins, rice bowls, milk tins (susu cap junjung) and cups were used as a measure for dried ingredients.

However, in Malaysia’s Culinary Heritage, we use weighing machines that calculates the international metric measures for weights (kilogram/kg and grams/g), volumes (litres and millilitres/ml) and lengths (centimetres/cm and millimetres /mm) as well as standard metric measuring cups and spoons.

Grinding and Pounding

Pestle and Mortar

Stone grinder

Before the advent of the blenders or food processors, our grandmothers would use the ‘Batu Giling’ (grinding stone) to grind chillies and spices finely and ‘Lesong’ (mortar and pestle) if the quantity is not large and a coarser texture is required. A good example is ‘Sambal Belacan’ where the chillies should not be too fine.

The batu giling consists of a thick, flat slab of stone and a cylindrical rolling pin. I can still hear grating and pounding accompanied with the ambrosial scent of fresh onions, ginger, herbs and spices at my grandmother’s kitchen. Whether it was the sound of a pestle crushing cloves and cinnamon sticks against a granite mortar or the piquant aroma emanating from fresh red chillies compressed on a grinding stone to kickstart a killer sambal, the rhythmic staccato eventually fades, resulting in the most amazing of meals displayed on the dining table.

Rice Grinder (boh)

Rice grinder

Today we can just go to the shop and buy the ground rice when we need it. In the old days, the rice had to be ground, using a boh. The boh is made up of two cylindrical blocks of granite. The bottom piece has a moat with a spout, and a square hole in the middle. The top cylinder has, off centre, a round hole going through from top to bottom. A wooden handle is fixed to the side of the top portion to turn it while a wooden or metal peg with a square bottom and a cylindrical top joins the square and round holes in the top and bottom parts of the boh. This is to keep the top block in place while it is rotated. (Nonya Heritage Kitchen, 2016, by Ong Jin Teong)

During our grandmother’s time, whenever she wanted to make apam, she would soak the rice overnight and then grind it the next day by hand using the boh. Nowadays we use readymade packaged rice flour. My grandmother’s white, pink and brown apam was soft, fluffy and split into four at the top. The secret lies in the batter. She made her own rice flour as it is best to mix rice flour, yeast, and palm sugar before pouring it into special little ceramic cups before steaming it, which makes the difference.

Coconut scraper (Kukur kelapa)

Coconut Scraper

Freshly squeezed coconut milk can easily be purchased from the market nowadays but not during our grandmother’s time. She had to scrape the coconut by using a coconut scraper. She first had to cut the fibrous husk from the coconut, break it into two, scrape the outer layer, then scrape using a coconut scraper to get the gratings. It is hard work and if you are not careful, you can cut your fingers. She would then add water, knead the gratings firmly and squeeze it through a fine strainer or a piece of muslin to produce the coconut milk.

Noodle maker (gebok)

Noodle Maker

In the good old days, our grandmother made laksa Johor with rice flour (tepong beras) instead of using spaghetti. She would first boil the rice flour and then mashed it before placing it in a brass (tembaga) container, called gebok. There are small holes at the bottom of the gebok while the surface of the inner wall was ringed in a spiral design. After placing the mashed rice flour inside the gebok, its head, which was like a screwdriver, would be pressed down. The head had a handle on top of it and when pressed down, strands of the white rice noodles would slowly ooze out.

Brass Kuali /Wok (Kuali Tembaga)

Brass Pot with Lid

Brass Kuali

Our grandmother had several brass kualis of various sizes for cooking some special dishes – rendang, harissa, halwa maskat, dodol and lempok. These brass kuali had to be used so that the heat is distributed evenly and slowly to prevent burning. Harissa, a Middle Eastern dish, has to be stirred until the mixture becomes thick, a process that can take hours. It also takes time and energy to make halwa maskat as the mixture has to be stirred for several hours, sometimes around 8 hours.

Grandma would place the kuali on a stove made of bricks. She would use rubberwood that had been chopped as rubberwood makes the best fire, giving it the right degree of heat.

To us nowadays, life must have been hard for our grandmother. Today’s wet markets and supermarkets offer an amazing selection of pre-prepared items which have reduced the time we need to spend in the kitchen – an important factor in our increasingly busy lives. Yet again today’s generation of grandmothers is more likely to be engaged in the workplace and trying to juggle home, family, work, hobbies, interests and travel abroad. Her time for cooking has been reduced and probably saves the traditional foods for special occasions and chooses quicker and healthier recipes in her day-to-day cooking. But it is good to know what our grandmother’s kitchen was like so we can really appreciate what we have today.

—

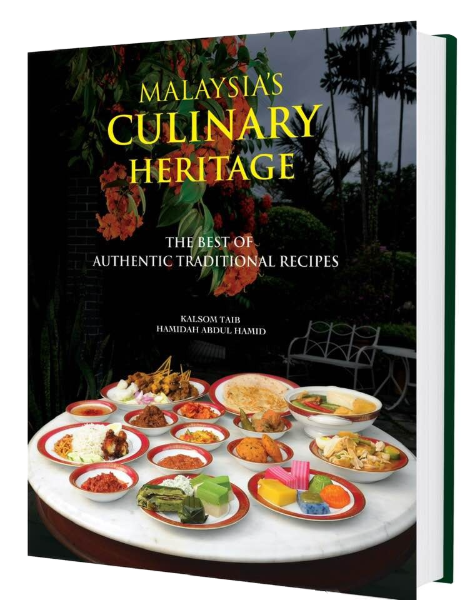

“Malaysia’s Culinary Heritage: The Best of Authentic Traditional Recipes”, is a compilation of 230 recipes that capture the unique flavours and textures of Malaysian food and place it among the world’s most varied and exciting cuisines. Out of the 230, 213 has been gazetted by the Department of National Heritage as traditional foods under the National Heritage Act (Act 645). Not only is it an album of nostalgic memories, giving a taste of Malaysia in both food and pictures, it is an important record, a distinguished culinary legacy for both present day and future generations of cooks.

To purchase the Malaysia’s Culinary Heritage Book,

WhatsApp us at +60173899250

—